11 KiB

Executable File

What the f*ck Python!

A collection of tricky Python examples

Python being an awesomoe higher level language, provides us many functionalities for our comfort. But sometimes, the outcomes may not seem obvious to a normal Python user at the first sight. Here's an attempt to collect such classic examples of unexpected behaviors in Python and see what exactly is happening under the hood! I find it a nice way to learn internals of a language and I think you'll like them as well!

Table of Contents

Table of Contents generated with DocToc

Checklist

[ ] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sH4XF6pKKmk [ ] https://www.reddit.com/r/Python/comments/3cu6ej/what_are_some_wtf_things_about_python/

👀 Examples

Example heading

One line of what's happening:

setting up

>>> triggering_statement

weird output

Explanation:

- Better to give outside links

- or just explain again in brief

datetime.time object is considered to be false if it represented midnight in UTC

from datetime import datetime

midnight = datetime(2018, 1, 1, 0, 0)

midnight_time = midnight.time()

noon = datetime(2018, 1, 1, 12, 0)

noon_time = noon.time()

if midnight_time:

print("Time at midnight is", midnight_time)

if noon_time:

print("Time at noon is", noon_time)

Output:

('Time at noon is', datetime.time(12, 0))

Explanation

Before Python 3.5, a datetime.time object was considered to be false if it represented midnight in UTC. It is error-prone when using the if obj: syntax to check if the obj is null or some equivalent of "empty".

is is not what it is!

>>> a = 256

>>> b = 256

>>> a is b

True

>>> a = 257

>>> b = 257

>>> a is b

False

>>> a = 257; b = 257

>>> a is b

True

💡 Explanation:

The difference between is and ==

isoperator checks if both the operands refer to the same object (i.e. it checks if the identity of the operands matches or not).==operator compares the values of both the operands and checks if they are the same.- So if the

isoperator returnsTruethen the equality is definitelyTrue, but the opposite may or may not be True.

256 is an existing object but 257 isn't

When you start up python the numbers from -5 to 256 will be allocated. These numbers are used a lot, so it makes sense to just have them ready.

Quoting from https://docs.python.org/3/c-api/long.html

The current implementation keeps an array of integer objects for all integers between -5 and 256, when you create an int in that range you actually just get back a reference to the existing object. So it should be possible to change the value of 1. I suspect the behaviour of Python in this case is undefined. :-)

>>> id(256)

10922528

>>> a = 256

>>> b = 256

>>> id(a)

10922528

>>> id(b)

10922528

>>> id(257)

140084850247312

>>> x = 257

>>> y = 257

>>> id(x)

140084850247440

>>> id(y)

140084850247344

Here the integer isn't smart enough while executing y = 257 to recongnize that we've already created an integer of the value 257 and so it goes on to create another object in the memory.

Both a and b refer to same object, when initialized with same value in same line

- When a and b are set to

257in the same line, the Python interpretor creates new object, then references the second variable at the same time. If you do it in separate lines, it doesn't "know" that there's already257as an object. - It's a compiler optimization and specifically applies to interactive environment. When you do two lines in a live interpreter, they're compiled separately, therefore optimized separately. If you were to try this example in a

.pyfile, you would not see the same behavior, because the file is compiled all at once.

>>> a, b = 257, 257

>>> id(a)

140640774013296

>>> id(b)

140640774013296

>>> a = 257

>>> b = 257

>>> id(a)

140640774013392

>>> id(b)

140640774013488

The function inside loop magic

funcs = []

results = []

for x in range(7):

def some_func():

return x

funcs.append(some_func)

results.append(some_func())

funcs_results = [func() for func in funcs]

Output:

>>> results

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

>>> funcs_results

[6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6]

//OR

>>> powers_of_x = [lambda x: x**i for i in range(10)]

>>> [f(2) for f in powers_of_x]

[512, 512, 512, 512, 512, 512, 512, 512, 512, 512]

Explaination

When defining a function inside a loop that uses the loop variable in its body, the loop function's closure is bound to the variable, not its value. So all of the functions use the latest value assigned to the variable for computation.

To get the desired behavior you can pass in the loop variable as a named varibable to the function which will define the variable again within the function's scope.

funcs = []

for x in range(7):

def some_func(x=x):

return x

funcs.append(some_func)

Output:

>>> funcs_results = [func() for func in funcs]

>>> funcs_results

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

Loop variables leaking out of local scope!

for x in range(7):

if x == 6:

print(x, ': for x inside loop')

print(x, ': x in global')

Output:

6 : for x inside loop

6 : x in global

But x was never defined ourtside the scope of for loop...

# This time let's initialize x first

x = -1

for x in range(7):

if x == 6:

print(x, ': for x inside loop')

print(x, ': x in global')

Output:

6 : for x inside loop

6 : x in global

x = 1

print([x for x in range(5)])

print(x, ': x in global')

Output (on Python 2.x):

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4]

(4, ': x in global')

Output (on Python 3.x):

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4]

1 : x in global

Explanation

In Python for-loops use the scope they exist in and leave their defined loop-variable behind. This also applies if we explicitly defined the for-loop variable in the global namespace before. In this case it will rebind the existing variable.

The differences in the output of Python 2.x and Python 3.x interpreters for list comprehension example can be explained by following change documented in What’s New In Python 3.0 documentation:

"List comprehensions no longer support the syntactic form

[... for var in item1, item2, ...]. Use[... for var in (item1, item2, ...)]instead. Also note that list comprehensions have different semantics: they are closer to syntactic sugar for a generator expression inside alist()constructor, and in particular the loop control variables are no longer leaked into the surrounding scope."

A tic-tac-toe where X wins in first attempt!

# Let's initialize a row

row = [""]*3 #row i['', '', '']

# Let's make a bord

board = [row]*3

Output:

>>> board

[['', '', ''], ['', '', ''], ['', '', '']]

>>> board[0]

['', '', '']

>>> board[0][0]

''

>>> board[0][0] = "X"

>>> board

[['X', '', ''], ['X', '', ''], ['X', '', '']]

Explanation

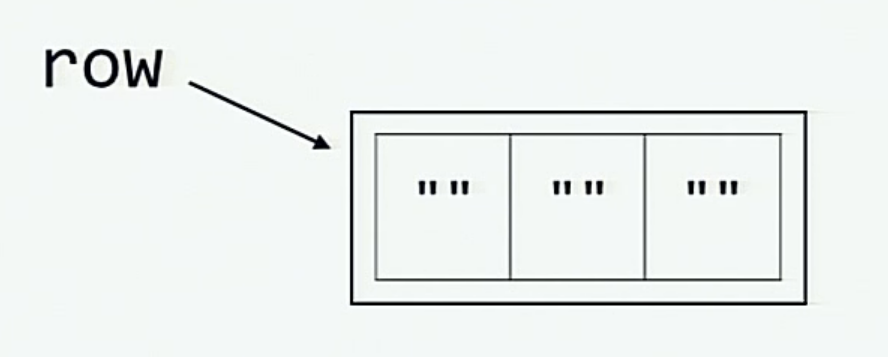

When we initialize row varaible, this visualization explains what happens in the memory

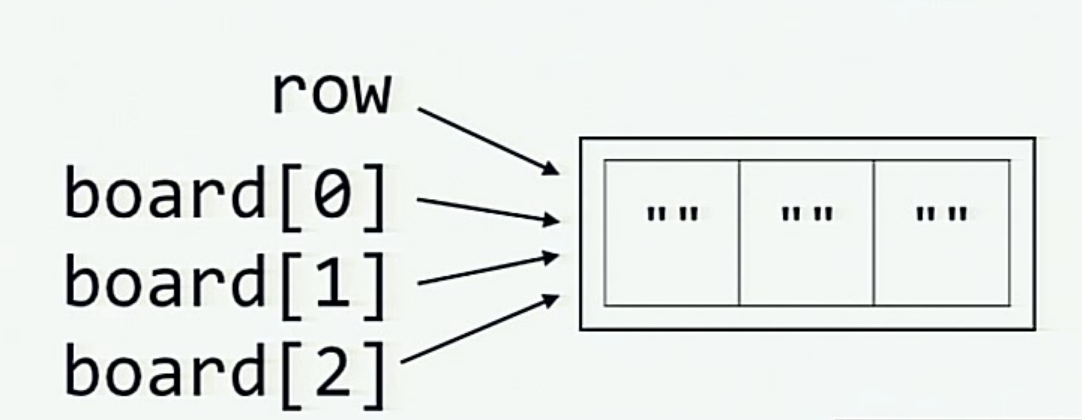

And when the board is initialized by multiplying the row, this is what happens inside the memory (each of the elements board[0], board[1] and board[2] is a reference to the same list referred by row)

Beware of default mutable arguments!

def some_func(default_arg=[]):

default_arg.append("some_string")

return default_arg

Output:

>>> some_func()

['some_string']

>>> some_func()

['some_string', 'some_string']

>>> some_func([])

['some_string']

>>> some_func()

['some_string', 'some_string', 'some_string']

Explanation

The default mutable arguments of functions in Python aren't really initialized every time you call the function. Instead, the recently assigned value to them is used as the default value. When we explicitly passed [] to some_func as the argument, the default value of the default_arg variable was not used, so the function returned as expected.

def some_func(default_arg=[]):

default_arg.append("some_string")

return default_arg

>>> some_func.__defaults__ #This will show the default argument values for the function

([],)

>>> some_func()

>>> some_func.__defaults__

(['some_string'],)

>>> some)func()

>>> some_func.__defaults__

(['some_string', 'some_string'],)

>>> some_func([])

>>> some_func.__defaults__

(['some_string', 'some_string'],)

A common practice to avoid bugs due to mutable arguments is to assign None as the default value and later check if any value is passed to the function corresponding to that argument. Examlple:

def some_func(default_arg=None):

if not default_arg:

default_arg = []

default_arg.append("some_string")

return default_arg

You can't change the values contained in tuples because they're immutable.. Oh really?

This might be obvious for most of you guys, but it took me a lot of time to realize it.

some_tuple = ("A", "tuple", "with", "values")

another_tuple = ([1, 2], [3, 4], [5, 6])

Output:

>>> some_tuple[2] = "change this"

TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignment

>>> another_tuple[2].append(1000) #This throws no error

>>> another_tuple

([1, 2], [3, 4], [5, 6, 1000])

Explanation

Quoting from https://docs.python.org/2/reference/datamodel.html

Immutable sequences An object of an immutable sequence type cannot change once it is created. (If the object contains references to other objects, these other objects may be mutable and may be changed; however, the collection of objects directly referenced by an immutable object cannot change.)

Using a varibale not defined in scope

a = 1

def some_func():

return a

def another_func():

a += 1

return a

Output:

>>> some_func()

1

>>> another_func()

UnboundLocalError: local variable 'a' referenced before assignment

Explanation:

When you make an assignment to a variable in a scope, it becomes local to that scope. So a becomes local to the scope of another_func but it has not been initialized previously in the same scope which throws an error. Read this short but awesome guide to learn more about how namespaces and scope resolution works in Python.

Contributing

All patches are Welcome! Filing an issue first before submitting a patch will be appreciated :)

Acknowledgements

The idea and design for this list is inspired from Denys Dovhan's awesome project wtfjs.

- Reddit Link

- Youtube video link