52 KiB

CORONA-WARN-APP SOLUTION ARCHITECTURE

This document is intended for a technical audience. It represents the most recent state of the architecture and is still subject to change as external dependencies (e.g. the framework provided by Apple/Google) are also still changing.

The diagrams reflect the current state but may also change at a later point in time. For some of the diagrams, Technical Architecture Modeling (TAM) is used.

Please note that further technical details on the individual components, the security concept, and the data protection concept are provided at a later date.

We assume a close association of a mobile phone and its user and, thus, equate the device (phone, app) and the person using it (person, user, individual) and use these terms interchangeably.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- BACKEND

- MOBILE APPLICATIONS

- RUNTIME ENVIRONMENT (HOSTING)

- CROSS-BORDER INTEROPERABILITY

- LIMITATIONS

- PRIVACY-PRESERVING DATA DONATION

INTRODUCTION

To reduce the spread of COVID-19, it is necessary to inform people about their close proximity to individuals that have tested positive. Without the use of digital solutions, health departments and affected individuals can only identify possibly infected individuals in personal conversations based on each individuals' memory or through manually maintained paper lists. This has led to a high number of unknown connections, e.g. when using public transport.

|

|---|

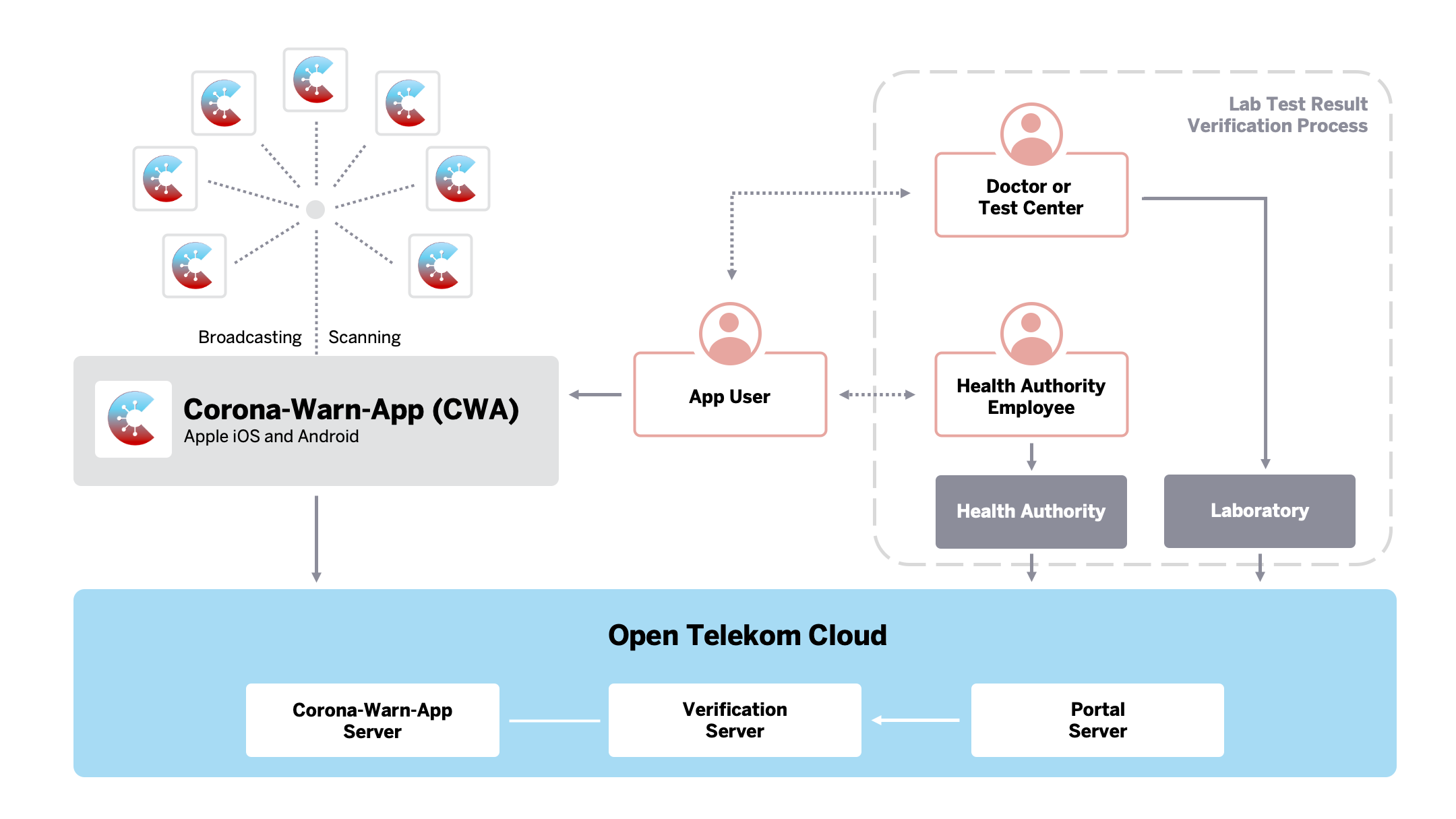

| Figure 1: High-level architecture overview |

The Corona-Warn-App (see scoping document), shown centrally in Figure 1, enables individuals to trace their personal exposure risk via their mobile phones. The Corona-Warn-App uses a new framework provided by Apple and Google called Exposure Notification Framework. The framework employs Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) mechanics. BLE lets the individual mobile phones act as beacons meaning that they constantly broadcast a temporary identifier called Rolling Proximity Identifier (RPI) that is remembered and, at the same time, lets the mobile phone scan for identifiers of other mobile phones. This is shown on the right side of Figure 1. Identifiers are ID numbers sent out by the mobile phones. To ensure privacy and to prevent the tracking of movement patterns of the app user, those broadcasted identifiers are only temporary and change constantly. New identifiers are derived from a Temporary Exposure Key (TEK) that is substituted at midnight (UTC) every day through means of cryptography. For a more detailed explanation, see Figure 10. Once a TEK is linked to a positive test result, it remains technically the same, but is then called a Diagnosis Key.

The collected identifiers from other users as well as the device's own keys, which can later be used to derive the identifiers, are stored locally on the phone in the secure storage of the framework provided by Apple and Google. The application cannot access this secure storage directly, but only through the interfaces the Exposure Notification Framework provides. To prevent misuse, some of these interfaces are subjected to rate limiting. If app users are tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, they can update their status in the app by providing a verification of their test and select an option to send their recent keys from up to 14 days back. On the Corona-Warn-App back-end server, all keys of individuals that have tested positive are aggregated and are then made available to all mobile phones that have the app installed. Additionally, the configuration parameters for the framework are available for download, so that adjustments to the risk score calculation can be made, see the Risk Scores section. Once the keys and the exposure detection configuration have been downloaded, the data is handed over to the Exposure Notification Framework, which analyzes whether one of the identifiers collected by the mobile phone matches those of the device of another individual that has tested positive. Additionally, the metadata that has been broadcasted together with the identifiers such as the transmit power can now be decrypted and used. Based on the collected data, the Exposure Notification Framework provided by Apple and Google groups exposures into 30 minute "exposure windows", which in turn can be used to determine the individual risk. Exposures are defined as an aggregation of all encounters with another individual on a single calendar day (UTC timezone). For privacy reasons, it is neither possible to track encounters with other individuals across multiple days, nor to link individual exposure windows to each other.

It is important to note that the persons that have been exposed to a positive tested individual are not informed by a central instance, but the risk of an exposure is calculated locally on their phones. The information about the exposure remains on the user’s mobile phone and is not shared.

The Corona-Warn-App pursues two objectives:

- It supports individuals in finding out whether they have been exposed to a person that has later been tested positive.

- It receives the result of a SARS-CoV-2 test on a user's mobile phone through an online system. This helps reduce the time until necessary precautions, e.g. a contact reduction and testing, can be taken.

In order to prevent misuse, individuals need to provide proof that they have been tested positive before they can upload their keys. Through this integrated approach, the verification needed for the upload of the diagnosis keys does not require any further action from the users. They only have to confirm in the app and for the Exposure Notification Framework that they agree to share their diagnosis keys. Manual verification is also possible if the lab that performed the testing does not support the direct electronic transmission of test results to the users' mobile phones or if users have decided against the electronic transmission of their test results.

PCR tests: Retrieval of Lab Results and Verification Process

Reporting positive tests to the Corona-Warn-App is crucial for informing others about a relevant exposure and potential infection. However, to prevent misuse, a verification is required before diagnosis keys can be uploaded. There are two ways for receiving this verification:

- Using the integrated functionality of the Corona-Warn-App to retrieve the results of a SARS-CoV-2 test from a verification server (see Figure 2, Step 4a). With this integration, the positive test result is already verified and the diagnosis keys can be uploaded right after the users have given their consent.

- Providing a human-readable token, e.g. a number or a combination of words, as verification to the app. This token is called teleTAN (see Figure 2, Step 4b).

|

|---|

| Figure 2: Interaction flow for verification process |

Figure 2 and Figure 3 illustrate the verification process. Figure 2 shows the interaction flow of the user and Figure 3 the flow and storage of data. Additions to the preexisting 'conventional' process through the introduction of the Corona-Warn-App and the integrated test result retrieval are marked blue in Figure 2.

This preexisting process for the processing of lab results includes that the doctor requesting the test also receives the results, so patients can be informed in a timely manner. As required by law (§9 IfSG), the responsible health authority (“Gesundheitsamt”) is notified by the lab about the test results as well. The notifications in case of a positive test includes, amongst others, the name, address, and date of birth of the positive tested individuals, so that they can be contacted and informed about the implications of their positive test. This is also represented in step 3 of Figure 2.

The flow for using the app is as follows, referencing the steps from Figure 2:

- Step 1: Users of the Corona-Warn-App (i.e. broadcasting and collecting RPIs)

- (1) When a test is conducted, they receive an information flyer with a custom QR code. The code is either created on-site or is already available as a stack of pre-printed QR codes. The QR code contains a globally unique identifier (GUID).

- (2) Optionally, they can scan the QR code with the Corona-Warn-App (Figure 3, step 1). If users decide against using the test retrieval functionality of the Corona-Warn-App, they still receive their test results through the regular channels explained before.

- (3) When the code is scanned, a web service call (REST) is placed against the Verification Server (Figure 3, step 2), linking the mobile phone with the data from the QR code through a registration token, which is generated on the server (Figure 3, step 3) and stored on the mobile phone (Figure 3, step 4).

- Step 2: The samples are transported to the lab together with a “Probenbegleitschein” which has a machine-readable QR code on it as well as other barcodes (lab ID, sample IDs).

- Step 3: As soon as the test result is available meaning the samples have been processed, the software running locally in the lab (lab client) transmits the test result to the Laboratory Information System together with the GUID from the QR code. The Laboratory Information System hashes the GUID and posts it together with the test result to the Test Result Server through a REST interface (Figure 3, step A), which in turn makes it available to the verification server.

- Step 4a: After signing up for notifications in step 1, the user’s mobile phone regularly checks the Verification Server for available test results (polling, figure 3, steps 5-8). This way, no external push servers need to be used. If results are available, the user is informed that information is available. The result themselves as well as recommendations for further actions are only displayed after the user has opened the app (see the scoping document for more details).

- If the test returns a positive result, users are asked to upload their keys to allow others to find out that they were exposed. If the users agree, the app retrieves a short-lived token (TAN) from the Verification Server (see also Figure 3, steps 9-13). As the Verification Server does not persist the test result, it is fetched from the Test Result Server once more (Figure 3, steps 10-11). The TAN is used as authorization in the HTTP header of the POST request for upload of the diagnosis keys of the last 14 days to the Corona-Warn-App Server (Figure 3, step 14).

- The Corona-Warn-App Server uses the TAN to verify the authenticity (Figure 3, steps 15-17) of the submission with the Verification Server.

- The TAN is consumed by the Verification Server and becomes invalid (Figure 3, step 16).

- If the Corona-Warn-App Server receives a positive confirmation, the uploaded diagnosis keys are stored in the database (Figure 3, step 18).

- The TAN is never persisted on the Corona-Warn-App Server.

- In case of a failing request, the device receives corresponding feedback to make the user aware that the data needs to be re-submitted.

|

|---|

| Figure 3: Data flow for the verification process |

Note regarding Figure 3 and Figure 4: The white boxes with rounded corners represent data storage. The HTTP method POST is used instead of GET for added security, so data (e.g. the registration token) can be transferred in the body.

As mentioned before, users might have decided against retrieving test results electronically, or the lab may not support the electronic process. Step 3 of Figure 2 shows that in these cases the health authority (“Gesundheitsamt”) reaches out to the patient directly. Also during this conversation, the teleTAN can be provided to the patient, which can be used to authorize the upload of diagnosis keys from the app to the Corona-Warn-App Server (step 4b of Figure 2). This process is also visualized in Figure 4. Whenever patients are contacted regarding a positive test result, they can choose to receive a teleTAN. The teleTAN is retrieved from the web interface (Figure 4, step 1) of the portal service by a public health officer. This service in turn is requesting it from the Verification Server (2-3). The teleTAN is then issued to the officer (4-5) who transfers it to the patient (6). Once the patient has entered the teleTAN into the app (7), it uses the teleTAN to retrieve a registration token from the Verification Server (8-10). Once the user has confirmed the upload of the Diagnosis Keys, the application requests a TAN from the server, using the registration token (11-13). This TAN is needed by the server to ensure that the device is allowed to do the upload. These TANs are not visible to the user. After uploading the TAN and the diagnosis keys to the Corona-Warn-App Server (14), the Corona-Warn-App Server can verify the authenticity of the TAN with the Verification Server (15-16) and upon receiving a confirmation, store the diagnosis keys in the database (17).

|

|---|

| Figure 4: Verification process for teleTAN received via phone |

The retrieval of the registration token ensures a coupling between a specific mobile phone and a GUID/teleTAN, preventing others (even when they have the QR code) to retrieve test results and/or to generate a TAN for uploading diagnosis keys. Upon the first connection with the Verification Server, a registration token is generated on the server and sent back to the client. In the information they receive, the patients should be asked to scan the QR code as soon as possible, as all further communication between client and server only uses the registration token which can only be created once. If a user deletes and reinstalls the app, the stored registration token is lost, making it impossible to retrieve the test results. In this case the fallback with the health authority workflow (through a hotline) needs to be used. From a privacy protection perspective, sending push notifications via Apple’s or Google’s push service is not acceptable in this scenario. Even though no specific test results are included in the notifications, the message itself signals that the user has taken a SARS-CoV-2 test. Thus, polling and local notifications are used instead. If a user also decides against local notifications, a manual update of the test results is also possible.

If a user did not receive a teleTAN from the health authority and/or has lost the QR code, a teleTAN needs to be retrieved from a hotline. The hotline ensures that users are permitted to perform an upload before issuing the teleTAN. It is then used as described before, starting from Figure 4, step 7.

Rapid Antigen Tests: Result Retrieval

While the PCR tests described before require a laboratory to receive the test results, Rapid Antigen Tests (RAT) can be evaluated shortly after taking the sample, at the Point of Care (PoC). Also the results for those Rapid Antigen Tests shall be transmitted to the Corona-Warn-App installed on the users' phones, so they can subsequently be used to warn others.

As the infrastructure for Rapid Antigen Tests is more distributed in comparison to PCR tests (i.e. locally and with regards to the operators: mobile test locations at venues, workplaces, etc., ), also the infrastructure for transmitting the test results needs to operate in a distributed way.

|

|---|

| Figure 5: End-to-end overview for Rapid Antigen Tests |

The overview contains two processes, one is part of the CWA scope, while the other belongs to a third party (the test provider).

The process flow shown assumes that users schedule an appointment on the provider's infrastructure (step 1-2), which is assigned an internal ID specific to the provider (step 3). The backend is then able to calculate a CWA Test ID (step 4) by applying a hash algorithm. Depending on the choice of the users, personal data may or may not be used to calculate the hash. The backend may then return a confirmation, which is then used to provide a QR-Code and/or link. With this QR-Code/link users can add the Rapid Antigen Test to their Corona-Warn-Apps. The CWA Test ID can then be validated locally (not as a means of security, but to make sure it is a valid code) using the exact same hashing algorithm as used on the backend (step 7). The test is then registered on the CWA infrastructure (step 8-11). The testing process itself, including the transmission to the providers backend (steps 12-20) takes place independently from the CWA infrastructure. The test result is linked to the CWA Test ID and transmitted to the CWA infrastructure (step 21-22).

Upload Schedule for Diagnosis Keys

A set of up to 15 Temporary Exposure Keys (TEK; called Diagnosis Keys when linked to a positive test) needs to be uploaded after the positive test result becomes available. The consent might have either been given when registering the test or after receiving the positive test result. In order to prevent that the TEK of the current day can be used to generate new RPIs after the submission, it is uploaded with a shorter validity (only until the point of submission) in comparison to the other Diagnosis Keys. To make sure that malicious third parties cannot use it to generate valid RPIs linked to a positive test, uploaded keys are not published immediately, but only after a defined safety period.

|

|---|

| Figure 6: Upload schedule for Temporary Exposure Keys (Diagnosis Keys) |

As users are not required to confirm negative test results, the functionality of uploading Diagnosis Keys on subsequent days remains theoretical. Each of those uploads could take place earliest at the end of each subsequent day (see (2) in Figure 6). It would require explicit consent of the user for each day and could take place up to the time when the person is not considered contagious anymore (but not any longer, as this would lead to false positives).

BACKEND

|

|---|

| Figure 7: Actors in the system, including external parties (blue components to be open-sourced) |

The Corona-Warn-App Server needs to fulfill the following tasks:

- Accept upload requests from clients

- Verify association with a positive test through the Verification Server and the associated workflow as explained in the “Retrieval of Lab Results and Verification Process” section and shown in the center of the left side of Figure 7.

- Accept uploaded diagnosis keys and store them (optional) together with the corresponding information (days since onset of symptoms/transmission risk level) into the database. Note that the transport of connection metadata (e.g. IP) of the incoming connections for the upload of diagnosis keys is removed in a dedicated actor, labeled “Transport Metadata Removal” in Figure 7.

- Provide configuration parameters to the mobile applications

- Threshold values for attenuation-based weighting

- Encoding and mapping of the Transmission Risk Level

- Threshold values for risk categories and alerts

- Weight mappings for the ENF (not used, but need to be present)

- Valid country codes for EFGS Visited Countries

- On a regular schedule (e.g. hourly)

- Assemble diagnosis keys into chunks for a given time period

- Store chunks as static files (in protocol buffers, compatible with the format specified by Apple and Google)

- Transfer files to a storage service as shown at the bottom of Figure 7 which acts as a source for the Content Delivery Network (CDN)

- Handle the integration with the European Federation Gateway Service which consists of:

- Downloading keys which are shared from connected countries and making them available for use by the CWA Mobile applications

- Upload relevant keys for DE to the service to share with other connected countries

- Expose a callback API which can be used by the EFGS to notify CWA when new key batches are available for download

- Handle the translation of keys values for DSOS and TRL

Those tasks relevant for interaction with the CWA Mobile application are visualized in Figure 8. Each of the swim lanes (vertical sections of the diagram) on the left side (Phone 1, Phone 2, Phone n) represents one device that has the Corona-Warn-App installed. The user of Phone 1 has taken a SARS-CoV-2 test (which comes back positive later). The users of Phone 2 and Phone n only use the functionality to trace potential exposure. The Corona-Warn-App Server represents the outside picture of the individual service working in the back end. For a better understanding, the database has been visualized separately.

|

|---|

| Figure 8: Interaction of the mobile application(s) with the back-end servers and CDN |

Note that even if a user has not been tested positive, the app randomly submits requests to the Corona-Warn-App Server (represented in Figure 8 by Phone 2) which on the server side can easily be ignored, but from an outside perspective exactly looks as if a user has uploaded positive test results. This helps to preserve the privacy of users who are actually submitting their diagnosis keys due to positive test results. Without dummy requests, a malicious third party monitoring the traffic could easily find out that users uploading something to the server have been infected. With our approach, no pattern can be detected and, thus, no assumption can be taken.

It could be possible to identify temporary exposure keys that belong together, i.e. belong to the same user, because they are posted together which results in them being in a sequential order in the database. To prevent this, the aggregated files are shuffled, e.g. by using an ORDER BY RANDOM on the database while fetching the data for the corresponding file. Alternatively, returning them in the lexicographic order of the RPIs (which are random) is a valid option as well. The latter might be more efficient for compressing the data afterwards.

The configuration parameters mentioned above allow the health authorities to dynamically adjust the behavior of the mobile applications to the current epidemiological situation. For example, the risk score thresholds for the risk levels can be adjusted, as well as how the individual data from exposure events influence the overall outcome of the risk assessment.

Further information can be found in the dedicated architecture documents for the Corona-Warn-App Server, the Verification Server, and the Portal Server.

Data Format

The current base unit for data chunks is one hour. Data is encoded in the protocol buffer format as specified by Apple and Google (see Figure 9). In case a data chunk does not hold any or too few diagnosis keys, the chunk generation will be skipped and the keys are made available as soon as the threshold has been passed.

The server makes the following information available through a RESTful interface:

- Available items through index endpoints

- Newly-added Diagnosis Keys (Temporary Exposure Keys) for the time frame

- Configuration parameters

- Parameters for configuring the risk Apple/Google Exposure Notification Framework

- Threshold values for attenuation-based weighting

- Risk score threshold to issue a warning

- Risk score ranges for individual risk levels

Return data needs to be signed and needs to contain a timestamp (please refer to protocol buffer files for further information). Using index endpoints will not increase the number of requests, as they can be handled within a single HTTP session. In case the hourly endpoint does not hold diagnosis keys for the selected hour, the mobile application does not need to download it. If, on the other hand multiple files need to be downloaded (e.g. because the client was switched off overnight), they can be handled in a single session as well.

In order to ensure the authenticity of the files, they need to be signed (according to the specifications of the API) on server side with a private key, while the app uses the public key to verify that signature. Exchange with other geographical regions takes place through the European Federation Gateway.

|

|---|

| Figure 9: Data format (protocol buffer) specified by Apple/Google |

The public key for verifying the signature is:

MFkwEwYHKoZIzj0CAQYIKoZIzj0DAQcDQgAEc7DEstcUIRcyk35OYDJ95/hTg3UVhsaDXKT0zK7NhHPXoyzipEnOp3GyNXDVpaPi3cAfQmxeuFMZAIX2+6A5Xg==

Data URL

Retrieving the data in a RESTful format, making it clearer to make it available through a transparent CDN (only requesting the files once).

If no diagnosis keys are available for the selected parameters, but the time frame has already passed, a signed payload with a timestamp and an empty list of diagnosis keys is returned. As this file is also signed by the server and, through the timestamp, is also different from other files without diagnosis keys, its authenticity can be verified.

Further details of the API are explained in the documentation of the Corona-Warn-App Server.

Data Retention

The data on all involved servers is only retained as long as required. Diagnosis Keys will be removed from the Corona-Warn-App Server when they refer to a period of more than 14 days ago. TANs on the Verification Server will be removed as soon as they have been used. The hashed GUID on the Verification Server needs to be retained as long as the GUID can be used to retrieve test results from the test result server. Otherwise, a second upload privilege, i.e. a registration token, could be fetched with the same GUID.

MOBILE APPLICATIONS

The functional scope of the mobile applications (apps) is defined in the corresponding scoping document. The apps are developed natively for Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android operating systems. They make use of the Exposure Notification Framework (ENF), e.g. for broadcasting and scanning for Bluetooth advertisement packages.

Supported Devices

For Apple devices an OS version of at least 12.5 (for older devices) or 13.7 is required for the system to work, as the framework is integrated into the operating system (see Figure 10).

|

|---|

| Figure 10: iOS Releases and ENF Support |

For Android devices, the features are integrated into the Google Play Services, which means that only this specific application needs to be updated for it to work. Devices starting with Android 6.0 (API version 23) and integrated BLE chips are supported.

ENF Usage

The Exposure Notification Framework (ENF) encapsulates handling of the keys, including all cryptographic operations on them, and broadcasting and scanning for Bluetooth advertisement packages for the app (see Figure 11 and Figure 12). The app itself does not have access to the collected exposures, i.e. the Rolling Proximity Identifiers, and is not notified by the framework if the collected exposures change. This includes events such as the collection of a new exposure or deletion of the exposure history. The only output of the ENF upon an infection is a collection of temporary exposure keys as shown in Figure 11. Those are subsequently called diagnosis keys.

|

|---|

| Figure 11: Architecture overview of the mobile application (focused on API usage/BLE communication) |

|

|---|

| Figure 12: Key flow from the sending perspective (as described in the specification by Apple/Google) |

The encapsulation especially applies to the part where matches are calculated, as the framework only accepts the diagnosis keys as input, matches them to (internally stored) RPIs and returns a list of exposure events without a link to the corresponding Rolling Proximity Identifiers (see Figure 13). With the use of the corresponding Associated Encrypted Metadata Key, the Associated Encrypted Metadata (AEM) of the captured RPI can be decrypted. This metadata contains the transmission power (which is used to calculate the attenuation).

|

|---|

| Figure 13: Key flow from the receiving perspective (as described in the specification by Apple/Google) |

All exposure events are collected by the ENF internally and are split up into "Exposure Windows", which represent all instances where one other specific device (without known identity) has been detected within a 30 minute window. If an encounter lasted for more then 30 minutes, multiple exposure windows are derived. Those cannot be related to each other neither can it be determined in which order (and possible overlap), exposures windows have occurred. This means that if for example five exposure windows are presented to the app by the ENF, it cannot be determined whether those have been five different devices or a single other device with 2.5 hours of contact. Same applies to the timely arrangement, i.e. all windows could have happened in parallel, with partial overlap or after one another.

|

|---|

| Figure 14: Exposure Windows |

Each exposure window contains the following information:

- infectiousness and report type - these parameters are attached to the respective diagnosis key by the sending app.

- day of the exposure - this parameter is determined by ENF based on when the respective RPI was received. Note that even though precise timestamp information exists in ENF, only the day itself is exposed (i.e. YYYY-MM-DD).

- multiple scan instances - this parameter represents occurrences where the other device has been actively identified during the scanning process. A scan instance consists of "seconds since last scan", i.e. for how long the other device was identified, and attenuation information as a measure of distance between the devices.

Risk Calculation

The Exposure Windows form the foundation of the risk calculation in the app. The result is an easy-to-understand risk level that is displayed to the user: low risk (i.e. green) or high risk (red). The details of the risk calculation, e.g. exposure windows or intermediate results, are not visible to the user. Further information regarding the individual exposure events (such as the matched Rolling Proximity Identifier, the Temporary Exposure Key or the exact time) remains within the secure storage of the framework and cannot be retrieved by the application.

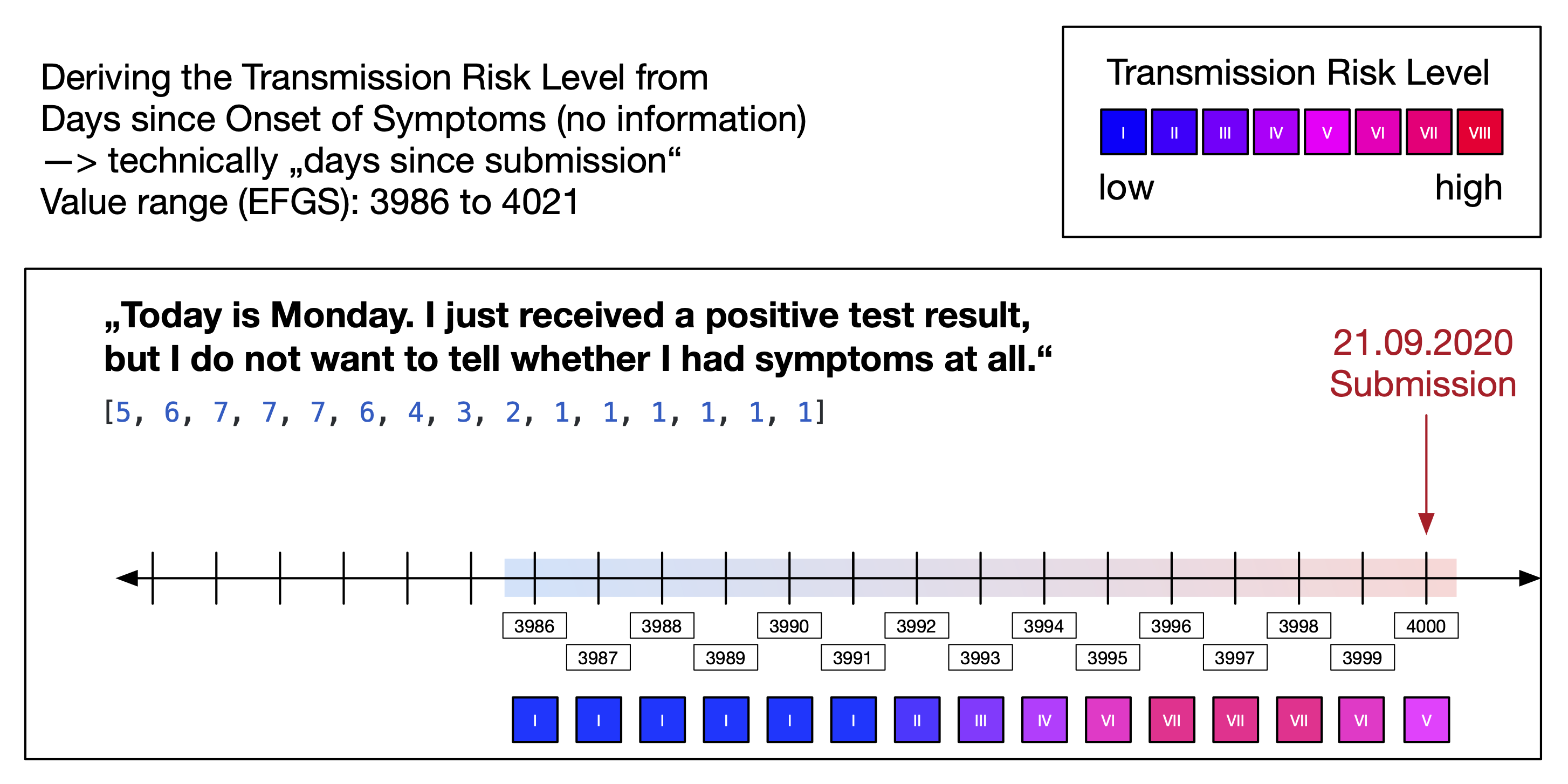

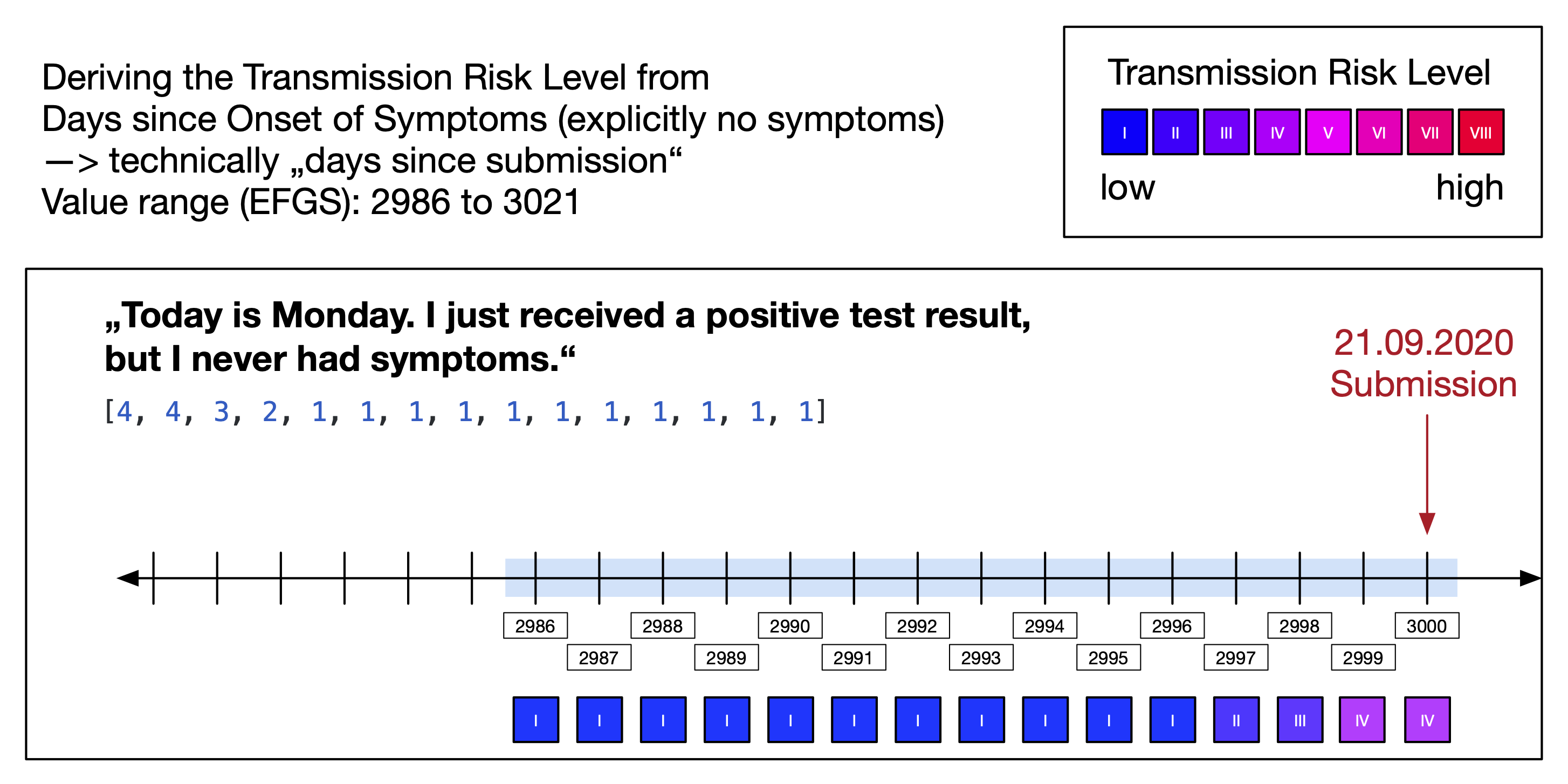

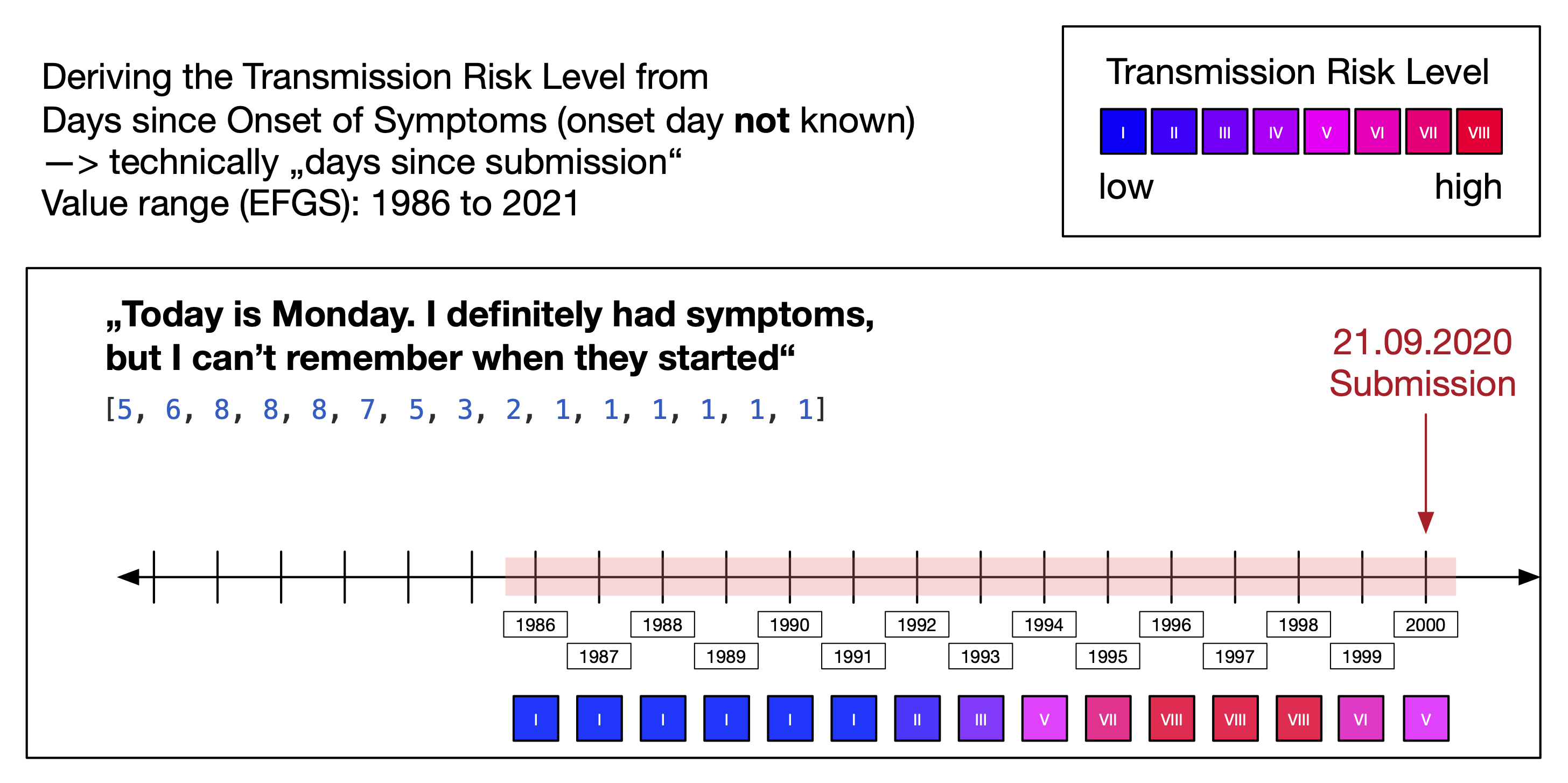

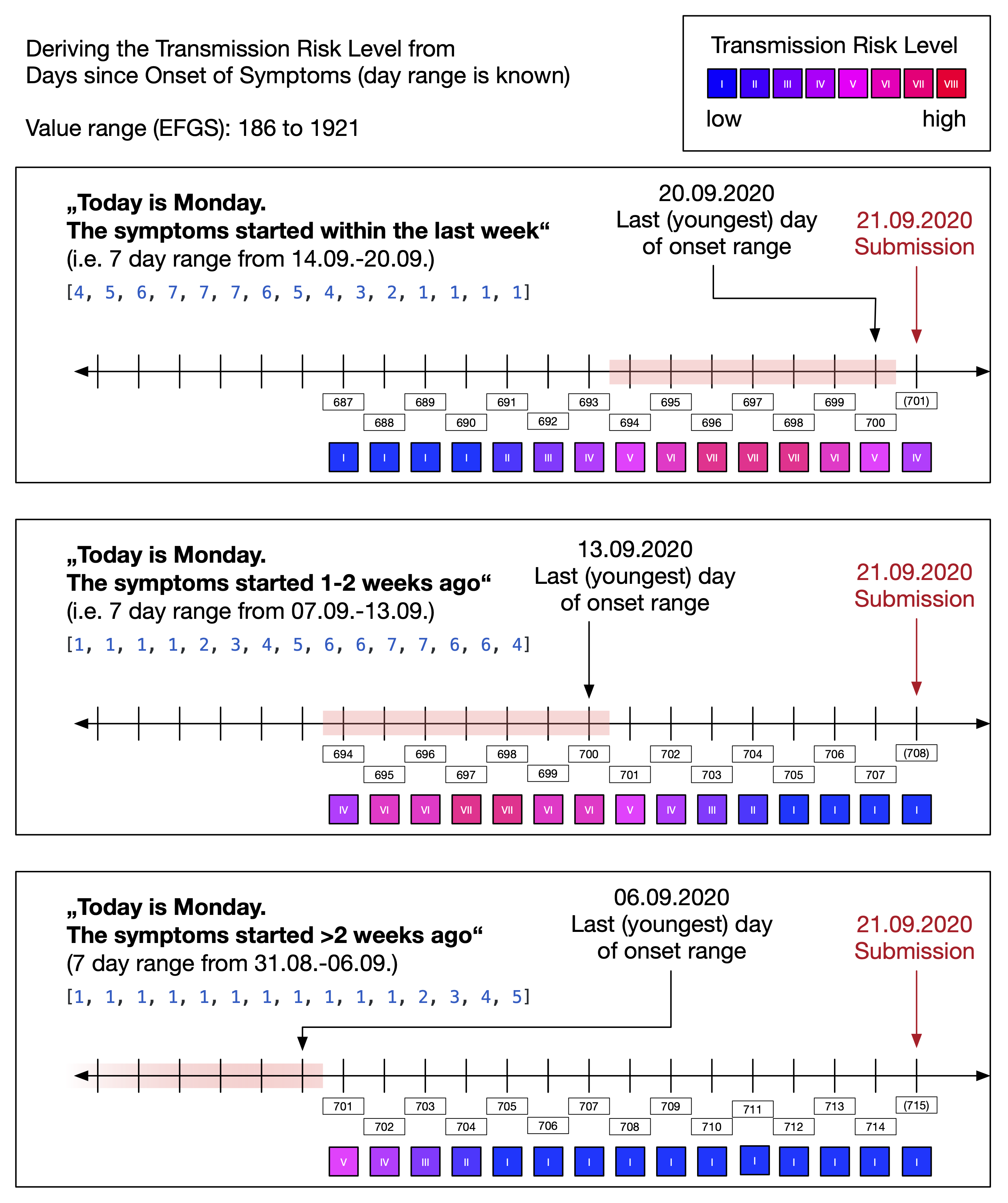

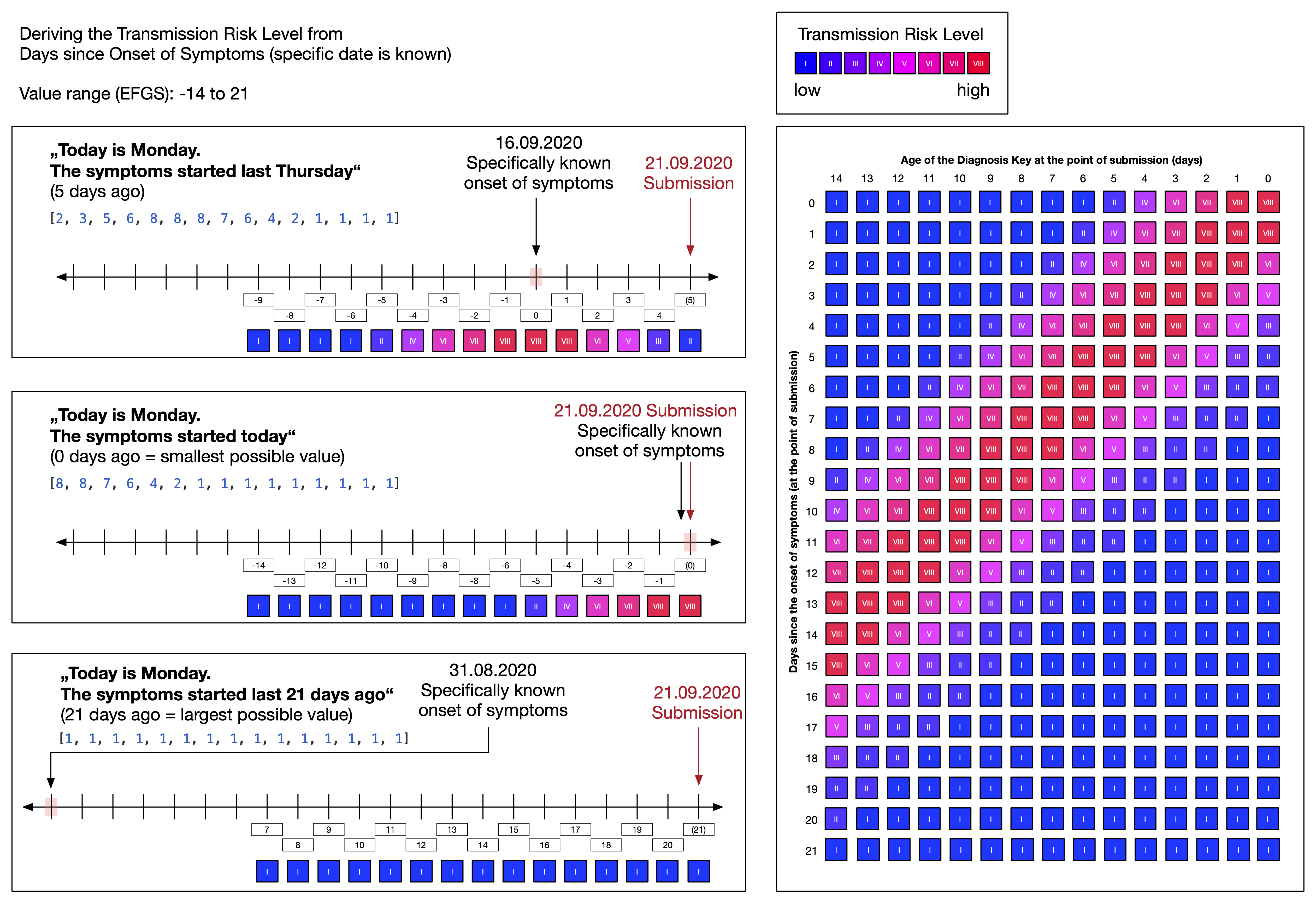

Within the risk calculation, the app can distinguish eight different "transmission risk levels" (TRL) of an exposure window. The TRL is a measure for the infectiousness of user of the sending app on a given day. While an exposure window already has a dedicated "infectiousness" parameter, the ENF effectively only allows two different values for it ("standard" and "high"); it cannot be used to represent eight values. The "report type" parameter has four different values and is irrelevant for the app in its original meaning (i.e. all exposures in the app are based on a "confirmed test" result). Therefore, the app uses the two possible values of the "infectiousness" parameter and the four possible values for the "report type" parameter to encode eight different TRLs. The mapping is described in Figure 15.

|

|---|

| Figure 15: Deriving the transmission risk level |

Note that Figure 15 shows that the "infectiousness" parameter itself is derived from "days since onset of symptoms" (DSOS). The DSOS is a relative measure and determined by the sending app for each diagnosis key based on the date to which a diagnosis key refers to and the date onset of symptoms (see also Days Since Onset of Symptoms).

Figure 16 displays how the total risk score is calculated from the exposure windows. The application is provided with a set of parameters, which are marked in blue within the figure.

Those parameters are regularly downloaded from the CWA Server, which means they can be modified without requiring a new version of the application (see risk-calculation-parameters-1.15.yaml for details).

In a first step, each exposure window is processed individually. The duration of each scan instance (i.e. "seconds since last scan") is weighted according to its attenuation. When those weighted durations are summed up, they are multiplied with the "transmission risk value" (which in turn is derived from the TRL described above). The result is a normalized exposure time on a specific day (e.g. "10 normalized exposure minutes on May 3 in a 30-minute window"). This information is used by the app to determine if an individual encounter (i.e. exposure window) by itself is a low or high risk exposure.

In a second step, the normalized exposure times are summed up by day (e.g. "20 normalized exposure minutes on May 3"). This information is used by the app to determine if the sum of all encounters on a given day is a low or high risk exposure.

|

|---|

| Figure 16: Risk calculation |

Note that the transmission risk level plays a special role in the above calculations: It can be defined by the app and be associated with each individual diagnosis key (i.e. specific for each day of an infected person) that is being sent to the server. It contains a value from 1 to 8, which can be used to represent a calculated risk defined by the health authority. As an example it could contain an estimate of the infectiousness of the potential infector at the time of contact and, hence, the likelihood of transmitting the disease. The specific values are defined as part of the app - a motivation of the parameter choices is found in the document Epidemiological Motivation of the Transmission Risk Level.

Days Since Onset of Symptoms

The "days since onset of symptoms" (DSOS) is a relative numeric measure that indicates the infectiousness of a diagnosis key. The reference point is the date of onset of symptoms that a user can provide when uploading diagnosis keys.

It is optional to provide information about the symptom onset and there different levels of granularity. This results in five different patterns for determining the DSOS of a diagnosis key and numeric values between -14 and 4000.

The different patterns are:

-

No information - the user declines to provide information about symptom onset

-

No symptoms - the user has no symptoms

-

No date information - the user has symptoms but declines to provide any date information

-

Date range - the user has symptoms and provides a date range (e.g. "within the last week", "1 to 2 weeks ago", "more than 2 weeks ago")

-

Specific date - the user has symptoms and provides a specific date

The DSOS value range -14 to 4000 encodes these different patterns for distribution of diagnosis keys via EFGS (see CROSS-BORDER INTEROPERABILITY).

When diagnosis keys are distributed for download by the app, a DSOS value is first mapped to a "transmission risk level" (see figures above) which is then encoded in the two parameters "days since onset of symptoms" and "report type" (see Risk Calculation).

Examples:

| DSOS during upload | DSOS pattern | Derived TRL | DSOS during distribution | Report Type during distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -1 | Specific date | VIII | 2 | Confirmed Test (1) |

| 1993 | No date information | III | 1 | Self Report (2) |

Data Transfer and Data Processing

In order to be able to regularly match the RPIs associated with positive tests (derived from Diagnosis Keys) against the RPIs stored in the framework, the mobile applications need to download the former regularly.

In order to prevent load peaks in the back end, the downloads need to be spread evenly across the set time interval (currently an hour). To achieve that, each client needs to randomly decide on a point of time within the given hour, when it will download the data. With a large number of clients, this should statistically lead to an even distribution of requests.

However, Apple’s background tasks don’t allow a specific point of time when the download task shall be distributed, but instead only let the developer define a minimum time interval after which the tasks should be executed. Even though exact execution times cannot be guaranteed, we expect a behavior as specified above.

To ensure that as few requests as absolutely necessary are made, the earliest point in time should be at the beginning of the next availability interval. A random number should be added to ensure that the earliest start dates are spread evenly across all clients. For an hourly interval this could be calculated as follows:

minimum seconds until execution = (seconds until beginning of next interval) + random(3600)

In some scenarios, it is possible that a client has been unable to retrieve data for one or more intervals. This might be due to the device being turned off, background activations not firing automatically (e.g. during the night, as described above), or unavailability of an internet connection. It is very important that the client ensures that after one of those breaks, all available data is being caught up to and a match for the last 14 days might be contained.

In case the download of the diagnosis keys and the exposure detection configuration from the server fails, the client application needs to retry gracefully, i.e. use a random time component for the retry, as well as extending retry intervals. However, it needs to be ensured that all diagnosis keys are downloaded from the server. Otherwise, possible matches could be skipped.

Further details can be found in the dedicated architecture documents for the mobile applications.

RUNTIME ENVIRONMENT (HOSTING)

The back end is made available through the Open Telekom Cloud (OTC).

For the operation of the back end, several bandwidth estimations need to be taken. As a high adoption rate of the app is an important requirement, we are considering up to 60 million active users.

Bandwidth Estimations

While each set of 14 diagnosis keys only has the small size of 392 bytes, all newly submitted diagnosis keys of a time period need to be downloaded by all mobile phones having the application installed. When considering 2000 new cases for a day, a transmission overhead (through headers, handshakes, failed downloads, etc.) of 100% and 30 million clients, this adds up to approximately 1.5MB per client, i.e. 42.8TB of overall traffic. If a day is split into 24 chunks (one per hour), this results in a total number of 720 million requests per day. If the requests are evenly spread throughout the corresponding hour, approximately 8,500 session requests per second need to be handled. Detailed descriptions of the connections can be found in the chapter "Data transfer and data processing". Those number exclude possible interoperability with other countries.

If the back end calls from the mobile applications cannot be spread as evenly as we expect, we might experience peaks. To achieve an even spread (and to be able to handle a peak), we will employ a Content Delivery Network (CDN) by T-Systems to make the individual aggregated files available. According to an evaluation with T-Systems, the estimated throughput and request number can be handled by their infrastructure.

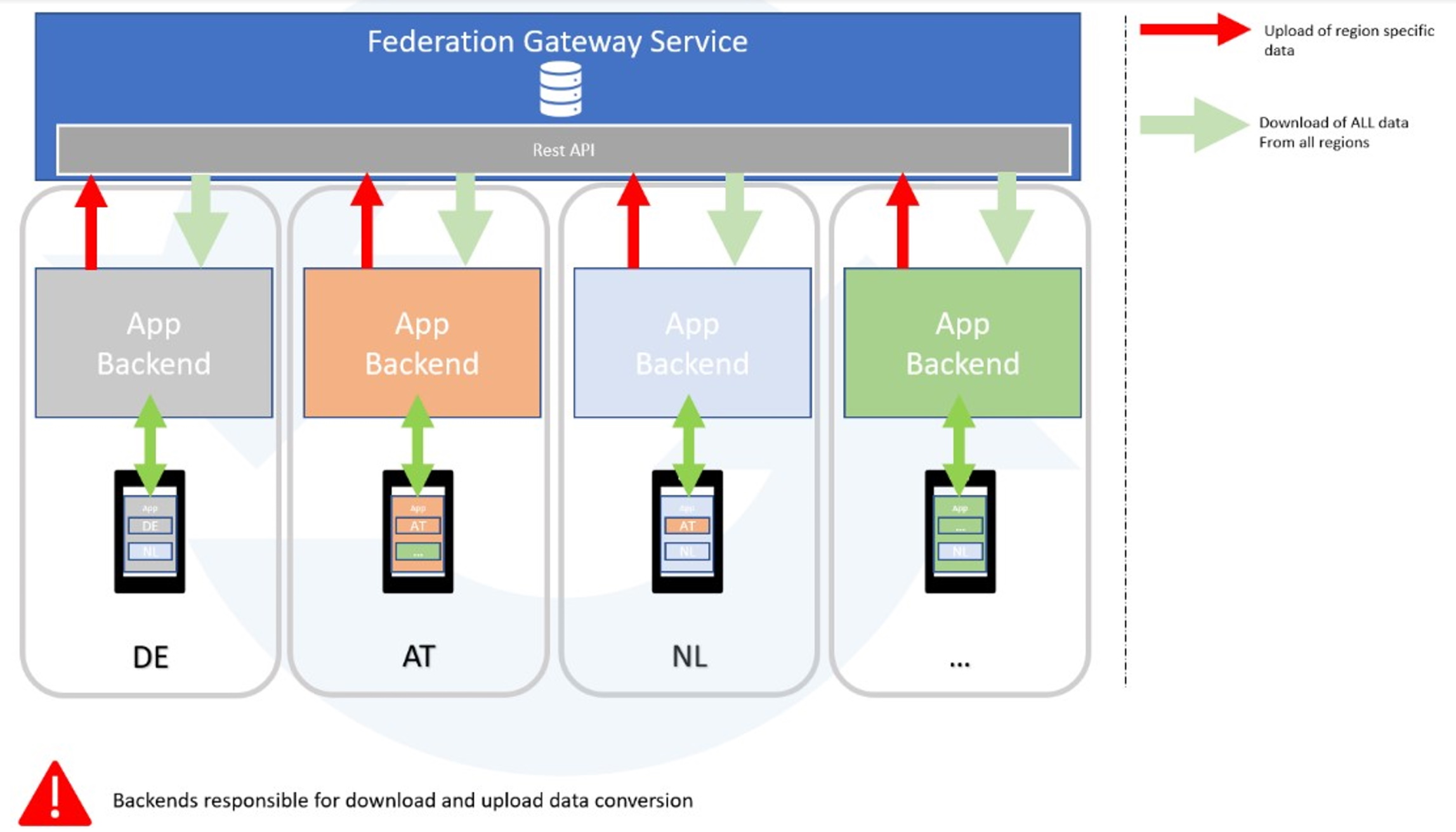

CROSS-BORDER INTEROPERABILITY

A definite prerequisite for compatibility is that the identifiers of the mobile devices can be matched, i.e. the GAEN framework by Apple and Google is being used.

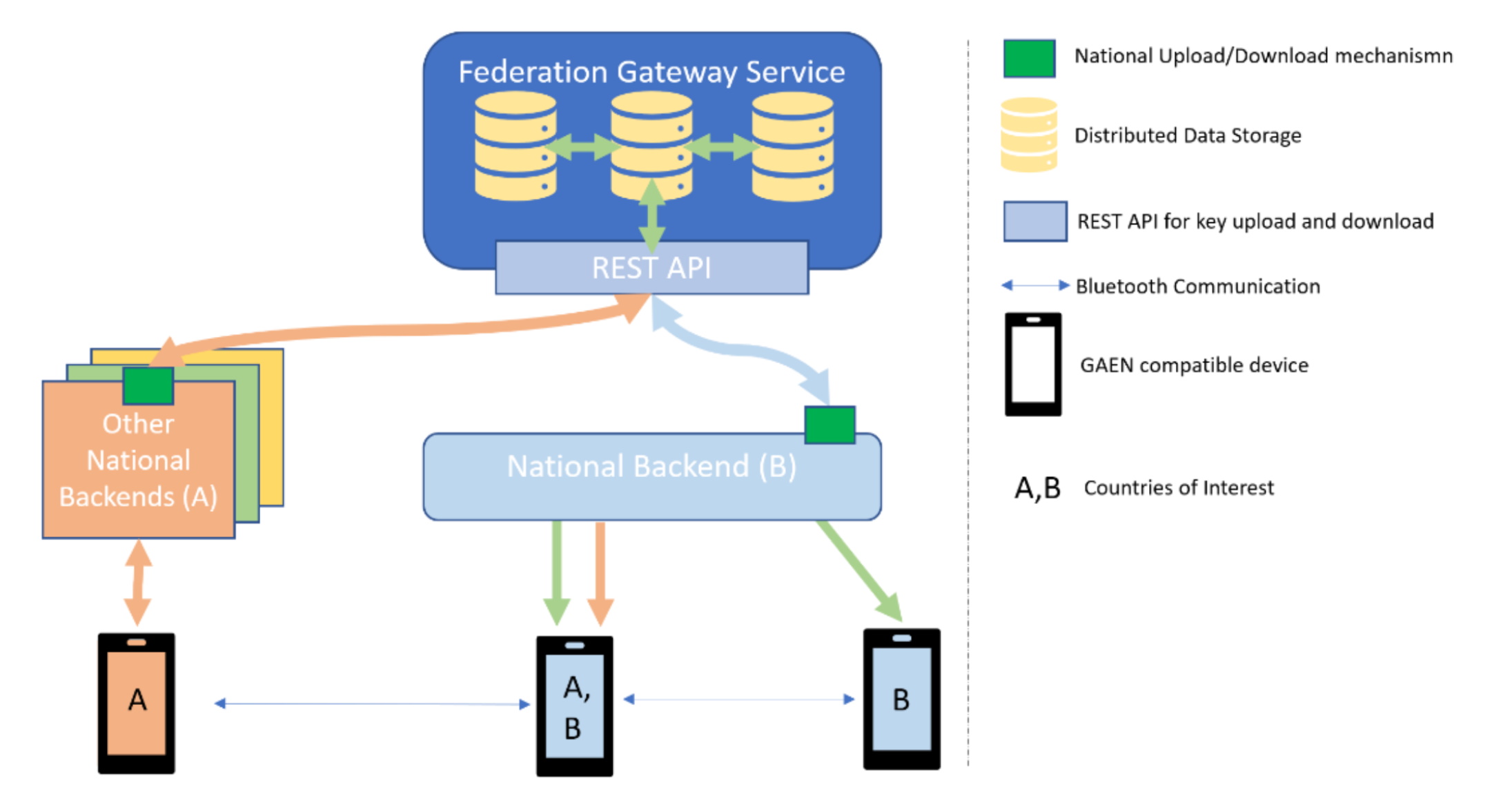

Most European countries are developing similar contact tracing apps. These apps may use the common frameworks by Google and Apple, enabling transmission and detection of GAEN format diagnosis keys between devices running different contact tracing applications. Each country has its own separate database, which contains the keys from infected individuals. In order to coordinate exposure information between countries, a common service is required to enable interoperability. The European Federation Gateway Service (EFGS) enables interoperability of diagnosis keys between the connected country backend servers.

|

|---|

| Figure 22: High-level EFGS overview |

The Federation Gateway Service facilitates backend-to-backend integration. Countries can onboard incrementally, while the national backends retain flexibility and control over data distribution to their users. For example, if a German citizen visits Italy and then becomes infected, the keys of the German citizen are then relevant for the citizens of Italy. In this case the German citizen keys would be shared with the EFGS to enable the French backend to obtain the keys. Similarly, if a French user is visiting Germany, that user's keys are of relevance to the German database.

|

|---|

| Figure 23: Autonomous National Backend |

In the example above, user A from country A travels to country B and afterwards tests positive. Only the relevant users (those which came within proximity of the infected user A) in Country B will receive the alert. Devices only communicate with their country's backend. That country's backend is then responsible to send relevant keys to the EFGS. All connected countries provide keys to the EFGS. The EFGS then makes available relevant keys to each additional connected country's backend. Notifications and alerts are handled by each individual country's backend. The EFGS stores information of all currently infected citizens along with a list of countries they visited. In order for the EFGS to function correctly, all users must specify their visited countries correctly (either manually or automatically).

LIMITATIONS

Even though the system can support individuals in finding out whether they have been in proximity with a person that has been tested positive later on, the system also has limits (shown in Figure 19) that need to be considered. One of those limitations is that while the device constantly broadcasts its own Rolling Proximity Identifiers, it only listens for others in defined time slots. Those listening windows are three minutes apart and are defined as being only very short. In our considerations we expect the windows to have a length of four seconds. A lower attenuation means that the other device is closer, while a higher attenuation might either mean that the other device is farther away (e.g. a distance of more than two meters) or that there is something between the devices blocking the signal. This could be objects such as a wall, but also humans or animals.

|

|---|

| Figure 24: Limitations of the Bluetooth Low Energy approach |

In Figure 24, this is visualized, while focusing on the captured Rolling Proximity Identifiers by only a single device. We are assuming that devices broadcast their own RPI every 250ms and use listening windows with a length of four seconds, three minutes apart. There are five other active devices – each representing a different kind of possible exposure. In the example, devices 3 and 4 go completely unnoticed, while a close proximity with the user of device 2 cannot be detected. In contrast to that very brief, but close connection with the user of device 5 (e.g. only brushing the other person in the supermarket) is noticed and logged accordingly. The duration and interval of scanning needs to be balanced by Apple and Google against battery life, as more frequent scanning consumes more energy.

It must be noted that some of the encounters described above are corner cases. While especially the cases with a very short proximity time cannot be detected due to technical limitations, the framework is able to detect longer exposures. As only exposures of longer duration within a certain proximity range are considered relevant for the intended purpose of this app, most of them are covered.

PRIVACY-PRESERVING DATA DONATION

The concept of Privacy-preserving Data Donation (PPDD) addresses the need to gain insight into the effectiveness of the Corona-Warn-App.

It consists of two components:

-

Event-driven User Surveys (EDUS) - allowing users to participate in a survey if they have received a warning about a high-risk encounter.

Among others, the survey contains questions regarding the user's behavior in the days preceding the warning and about next steps the user might take, such as seeing a doctor, taking a test, etc.

-

Privacy-preserving Analytics (PPA) - allowing users to share metrics of the risk calculation, test result delivery, and key submission behavior.

For example, this includes the current risk level and date of the most recent encounter or whether a test has been registered, how long it took until the result was made available.

Both EDUS and PPA are separate and optional features that require users to actively opt-in. No data is collected without prior consent and any pending data is discarded once a consent is withdrawn.

A dedicated CWA Data Donation Server processes the requests relating to Privacy-preserving Data Donation. Access to the APIs is restricted to the Corona-Warn-App by a concept called Privacy-preserving Access Control (PPAC). It requires clients to provide an authenticity proof of the device and of the Corona-Warn-App. The access is denied if the authenticity proof is not valid.

The authenticity proof is OS-specific and uses native capabilities:

-

iOS clients leverage the Device Identification API to authorize an API Token for the current month; the use of the API Token is rate-limited

-

Android clients leverage the SafetyNet Attestation API to provide an integrity verdict about the device and the client

The following diagram shows the individual components and their interaction:

|

|---|

| Figure 25: Privacy-preserving Data Donation |